Majority of students say they’re AGAINST suggested change to fees

It's one of the more high-profile student finance changes likely to be debated by government, but the majority of students are against it.

Credit (foreground): Cash Money Records Inc

Theresa May's announcement of a year-long review into student fees and finance has reignited the debate on how the system should change, but one major suggestion has already been given the seal of disapproval by students.

Education Secretary, Damian Hinds, had put forward the idea that tuition fees should reflect each degree's value "to our society as a whole".

Under such a system, degrees with clearer and higher-paid career paths, such as Engineering or Medicine, would cost more than those that don't, such as English and History.

However, less than a week after the suggestions hit the headlines, a survey by the Higher Education Policy Institute (HEPI) has found that a massive 63% of students are against the proposal, with just 33% in favour and 4% unsure.

The results of the survey will no doubt come as a blow to the government, whose decision to conduct a major review into student fees and finance has been seen by many as a direct response to the huge turnout of young voters in support of Labour at the last election.

Is it ok to charge more for some degrees?

Credit: ABC

While the majority of students polled said that full-time courses should all have the same fees, when pushed for greater detail, the results started to shift a little.

Just over half (52%) said that it might be justified to charge higher fees for Medicine, and 39% believed that subjects such as English and History should have lower fees. Contrastingly, just 7% supported higher fees for these arts subjects, and 6% for modern languages.

The survey also asked students for their preference, should a system of varying fees be introduced. The majority (57%) backed higher fees for courses that cost more to teach, with 17% in favour of charging more for courses with higher earning potential, and 7% saying fees should be increased at more prestigious universities.

When asked whether or not students from poorer backgrounds should get a reduction in fees (a proposal >we reported on last year), 59% of those polled were against the idea, compared to 38% in favour.

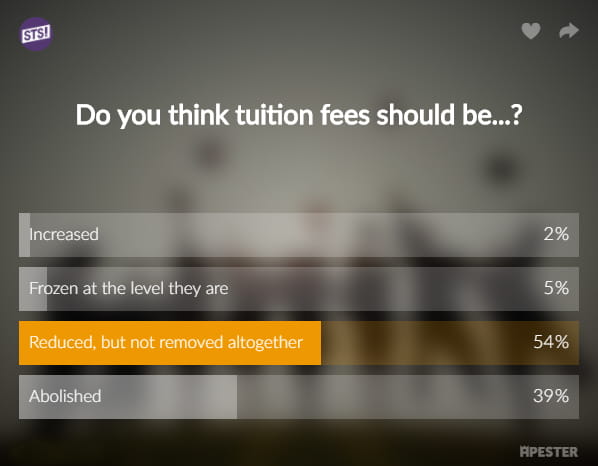

In our report on Theresa May's announcement, we asked you what you feel should be done about tuition fees. Interestingly, at the time of writing, the most popular solution is to decrease fees, but not abolish them altogether. Who'd have thought?!

Value for money, or creating social inequality?

Credit: 20th Century Fox

During her speech on Monday, Theresa May called for better value for students. According to the prime minister, the current system has failed to deliver sufficient competition on price, and that "the level of fees charged do not relate to the cost of quality of the course".

Although she hasn't explicitly come out in favour of charging different fees for different degrees, these comments would seem to suggest that she's open to the idea of it.

Supporters of the proposed system argue that it's a fairer way of charging for tuition, as currently a student with eight contact hours a week and an expected graduate salary of around £15,000/year pays the same fees as a student with well over 20 hours of contact and a graduate salary of over £30,000/year.

It's certainly a compelling argument, and in reality, tuition fees can already be varied. Almost every course charges £9,250/year, but this is merely a cap. The government hasn't told universities to charge the maximum amount, although some would argue that their hands have been forced by funding cuts elsewhere.

I feel like a broken record, but I'll say it again: the real issue is the disconnect between the cost of university (the fees) and what a student actually repays.

Those who get high earning jobs generally end up paying back the most towards their degree already. In fact, the top 25% of earners are the only ones who will end up paying off their whole loan under the current system.

Let's look at a really quick example. Imagine they reduced the fees on humanities degrees to £5,000 per year. If that student has a starting salary of £25,000 they'll repay the same amount towards their degree as they would with the fees at £9,250. Don't believe me? Try it for yourself here.

The commercialisation of university education is upon us. The fact that policies like this are being debated is a real concern.

Jake Butler, Save the Student's student finance expert

Opponents of the scheme believe that it will cause more harm than good when it comes to creating a fairer education system.

They argue that decreasing fees for degrees with lower earning potential and 'less value' to "society as a whole", or increasing them for courses with more, will simply persuade students from poorer backgrounds to go for the cheapest option.

As graduates of these degrees typically earn less money, there's a risk that varying tuition fees could serve to keep the poor, poor.

Others argue that earning potential shouldn't even be a consideration, and that a university education is about pursuing an interest in a subject that you're interested in. Regardless of their economic background, students shouldn't be put off studying a course because of the price tag.

Would varying fees actually harm students?

If this system is introduced (and remember that it's only a suggestion, and there's a whole year's worth of debate still to come!), it's worth noting that in practice, the amount of student debt you have isn't actually a huge burden.

We're fully in favour of cutting fees and increasing financial support for students, but the current loan repayment system is actually pretty cushy.

Regardless of how big or small your debt is, you only ever repay 9% of however much you earn over the threshold (£21,000, rising to £25,000 in April). What's more, the debt is cancelled 30 years after you graduate, and it's estimated that 77% of students won't have paid back their loans in full by this point.

In other words, whether you choose to study an English degree that costs £7,000/year, or a Medicine degree that costs £12,000/year, your monthly repayment will still be 9% of your earnings over the threshold.

Should your earnings drop below the threshold, you'll stop making repayments until you're back above it. What's more, whether you reach the 30 year mark with £40,000 or £40 still to pay back, your debt will be cancelled.

That said, there is undeniably a huge psychological factor when it comes to tuition fees. If one degree costs significantly less than another, it's natural to feel that the cheaper one is more affordable – regardless of the fact that the current repayment system makes them all equally affordable.

So if you come from a poorer background, there's every chance that unless you're well-versed in the realities of student finance (and very few people are), you might feel pushed into studying a cheaper course. And we're sure that you don't need us to tell you that that is not a fairer system.

Check out the Big Fat Guide to Student Finance for everything you need to know about fees and finance.